Ministerial directions

Ministerial directions are formal instructions telling departments to proceed with a spending proposal, despite objection from permanent secretaries.

What are ministerial directions?

Ministerial directions are formal instructions from ministers telling their department to proceed with a spending proposal, despite an objection from their permanent secretary.

Each permanent secretary – the most senior civil servant in each department – is also the ‘accounting officer’ for their department: the person who parliament would call to account for how the department spends its money. They have a duty to seek a ministerial direction if they think a spending proposal breaches any of the following criteria:

- Regularity – if the proposal is beyond the department’s legal powers, or agreed spending budgets

- Propriety – if it doesn’t meet ‘high standards of public conduct’, such as appropriate governance or parliamentary expectations

- Value for money – if something else, or doing nothing, would be cheaper and better

- Feasibility – if there is doubt about the proposal being ‘implemented accurately, sustainably or to the intended timetable’

The permanent secretary of a department writes to their secretary of state expressing their concerns, seeking a direction. They are able to cite multiple criteria when requesting a direction.

In response, the ministerial direction instructs the permanent secretary to implement the decision. As a result of this direction, the minister, not the permanent secretary, is now accountable for the way the money is spent.

How often do ministerial directions happen?

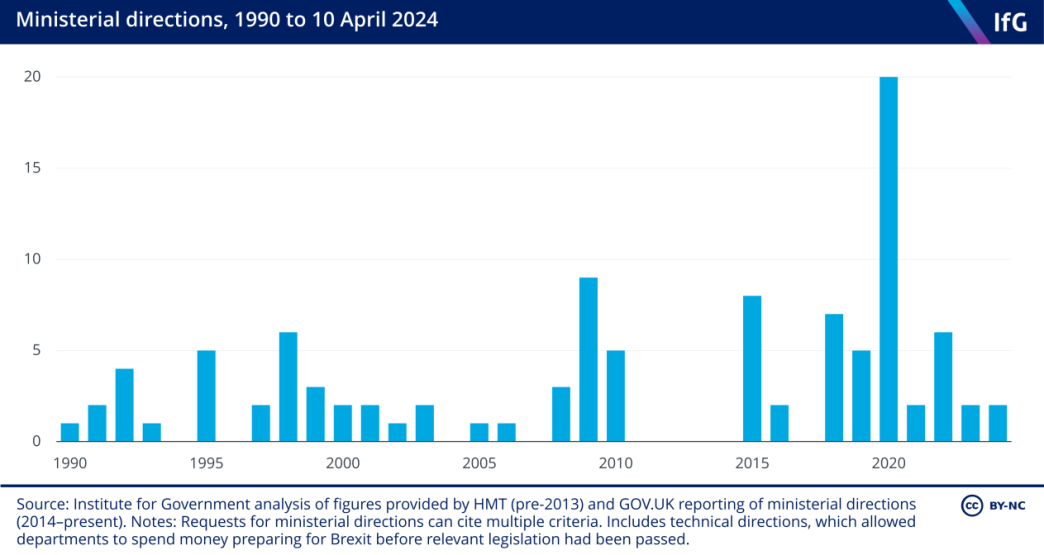

Ministerial directions do not happen that often. We know the details of 104 since 1990, 54 of those since the 2010 election.

It is sometimes said that more are issued in the run-up to an election, but this isn’t really the case. The main exception was before the 2010 election, when 14 directions were issued in two years. This was due to an expected change of government, and responses to the financial crisis – in the form of fiscal stimulus measures and bank bailouts – which broke normal rules.

On what issues are ministerial directions made?

In recent years, Brexit and Covid-19 have led to an increase in the number of ministerial directions issued. In 2018, four technical directions were issued to allow departments to spend money in preparation for Brexit before legislation had been passed – they operated much like traditional ministerial directions. And between 2020 and 2022, ministers issued 15 directions in relation to the coronavirus pandemic.

One of the more famous ministerial directions was issued on the Pergau Dam affair in 1990. undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction In this instance, funding for a project in Malaysia was deemed not only a poor use of development aid money but – given its connection to arms sales – also illegal under UK law. This affair eventually led to the introduction of the ‘value for money’ criterion which replaced an ill-defined requirement for public spending to be ‘prudent and economical’.

Since the Grenfell Tower fire in June 2017, there have also been four ministerial directions relating to funding the removal of unsafe cladding and the installation fire alarms. undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction All four were requested on the grounds of value for money.

In June 2020, Boris Johnson issued a ‘personal minute’, relating to a ‘compensation payment’ of almost £250,000 to outgoing cabinet secretary and national security adviser, Sir Mark Sedwill. Although it was not officially labelled as a ministerial direction, the minute formally directed Alex Chisholm (permanent secretary at the Cabinet Office) to make the payment – Chisholm had advised that the prime minister would have to make the decision since Chisholm reported to Sedwill and therefore could not ‘bring to bear the independent judgment required’. undefined Civil Service World, ‘A sense of direction’, Civil Service World, 28 March 2012, retrieved 26 January 2022, www.civilserviceworld.com/in-depth/article/a-sense-of-direction This has been included in our charts in the category of ‘unclear/other’.

In April 2022, then home secretary Priti Patel issued a ministerial direction to the permanent secretary at the Home Office, Matthew Rycroft, on the government’s planned migration and economic development partnership with the government of Rwanda. The controversial policy involves processing individuals’ asylum claims, which are inadmissible under the UK’s current asylum system, in Rwanda. The ministerial direction was requested by Rycroft on the grounds of value for money. He claimed there was insufficient evidence “to demonstrate that the policy will have a deterrent effect significant enough” to justify its cost.

More recently, then-business secretary Jacob Rees-Mogg issued two ministerial directions in 2022 on the government’s response to the energy crisis, and in April 2024 Steve Barclay, the environment secretary, issued a ministerial direction to set up a compensation scheme for fishers affected by restrictions on the catching of pollack. 4 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, ‘Pollack compensation scheme: ministerial direction’, 10 April 2024, www.gov.uk/government/publications/pollack-compensation-scheme-ministerial-direction Defra permanent secretary Tamara Finkelstein had requested a direction on the grounds of value for money.

Do some departments have more ministerial directions than others?

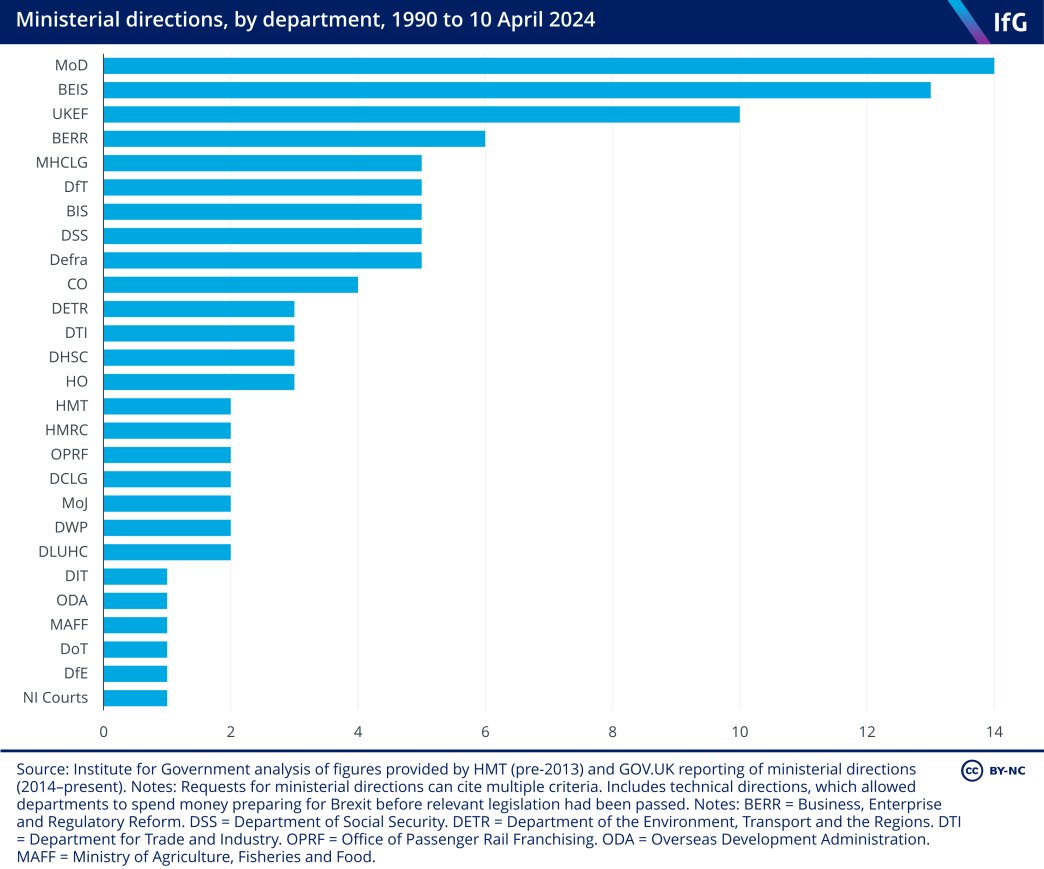

Since 1990, ministers at the Ministry of Defence have issued the most directions at 14, although there have been none since early 2010.

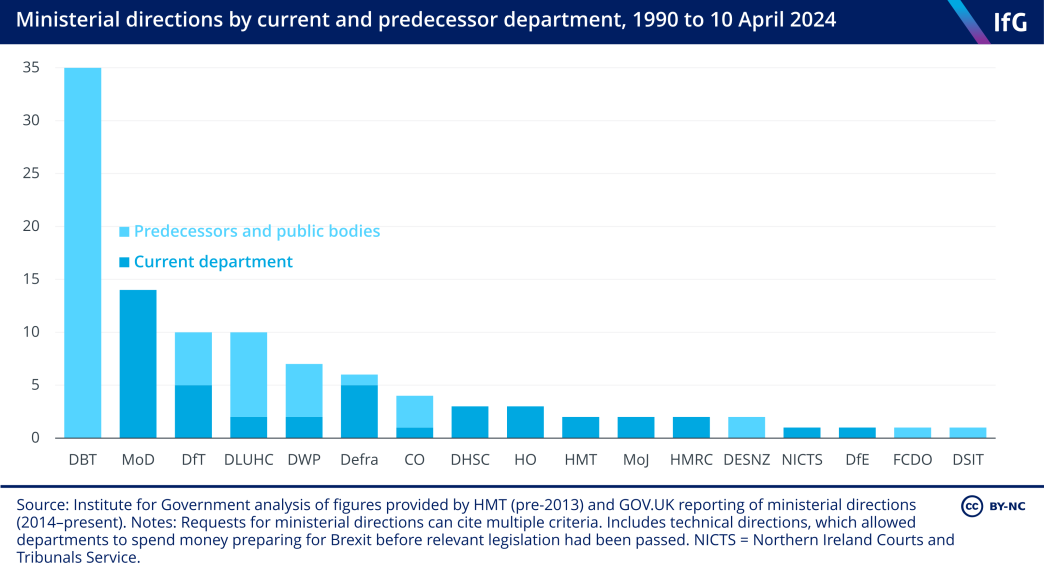

Grouping current departments with their predecessor bodies and agencies shows that defence, business, trade and industry and transport are the areas with the most directions since 1990. Since 2010, business and transport have dominated.

Three of the directions from Cabinet Office were issued by the prime minister. The first was issued by David Cameron on special adviser pay in 2016. The second was a direction from Boris Johnson that the government should defend a legal case brought by a former special adviser regarding their dismissal, rather than seek a settlement. And the third was also issued by Johnson – as noted above – on a ‘compensation payment’ for Sir Mark Sedwill after he stepped down as cabinet secretary and national security adviser in June 2020.

Why have these ministerial directions been issued?

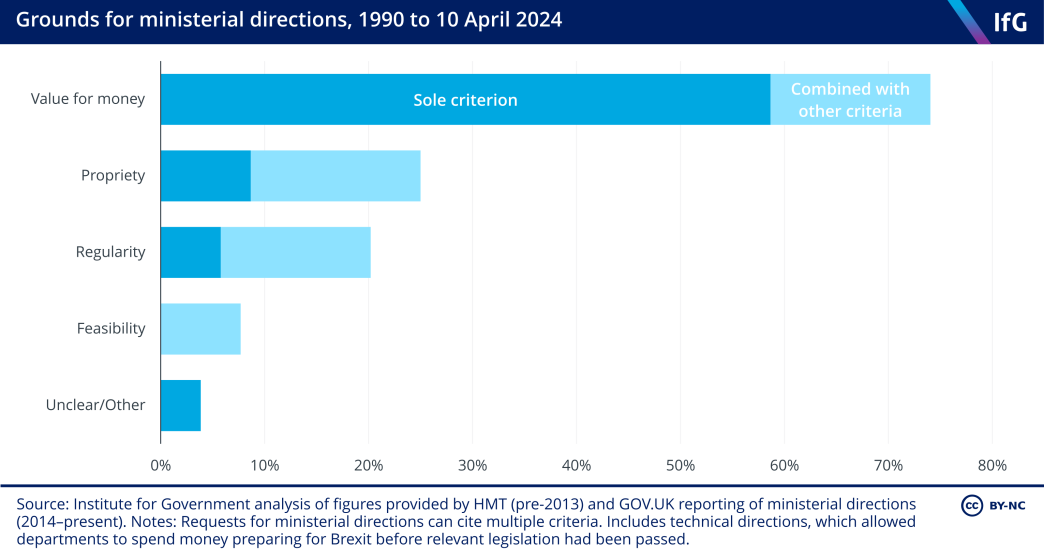

The vast majority of ministerial directions issued since 1990 have been on value for money grounds, either alone or in conjunction with other criteria. Only six directions have ever been issued solely on regularity grounds (the first was in 2019), while the first direction to include feasibility as a reason (it was only introduced in 2011) was issued at DfE in 2018.

Across March, April and May 2020 a series of ministerial directions were issued at BEIS, which included the first ministerial directions to include three of the grounds at once, and one direction (on the local authority discretionary grants fund) which included all four grounds (value for money, feasibility, propriety and regularity). Defra issued the second ministerial direction including all four grounds in December 2020.

How and when do we know about ministerial directions?

Before the rules were changed in 2011, directions could remain secret for years. Since then, departments have been required to publish the existence of a direction – though not the direction itself – no later than when they publish their annual accounts. They must tell the Treasury, who must tell the Comptroller and Auditor General (the head of the National Audit Office), who then tells the Public Accounts Committee.

Recent directions have been published on GOV.UK relatively soon after they’ve been issued – generally between a few days and a few months after they have been issued. One direction issued by Johnson on legal proceedings brought by a special adviser was not published until nine months after it had been issued, after the legal proceedings had concluded.

Are ministerial directions a sign of failure?

One former permanent secretary told the Institute for Government that they would have regarded asking for a direction as a professional failure. In their view, directions suggest a lack of confidence in ministerial decisions, and show a public rift in what is supposed to be a private working relationship.

However, this is not the view of many ministers and permanent secretaries involved in issuing them, and has become even less the case in recent years. For example, many of the ministerial directions issued during the Covid-19 pandemic state the schemes in question were good public policy and necessary to help the economic recovery of the UK, but the permanent secretaries were required to flag them nonetheless. Recently, ministerial directions have been issued in relation to policies where officials felt they were unable to meet their obligations because of the speed and size of spending but where ministers were clear they wanted to proceed – such as the energy price guarantee and relief scheme in late 2022.

The issuing of a direction – even over small sums of money, such as £500 in the case of a Ministry of Defence direction in 2000 – may also be seen as the accountability rules being taken seriously and the system doing its job.

Some civil servants have told the Institute for Government that the ‘threat’ of a ministerial direction can be effective. The conversation about one – especially over value for money – can be a useful tool for permanent secretaries trying to help improve ministerial plans.

One former permanent secretary put it to us, “I did say on not a completely trivial number of occasions, ‘If you were to persist in going down this route, Secretary of State, I could get to a point where I might have to seek a direction from you.’” This had, in their view, a ‘galvanising effect’ on discussions to avoid a direction being sought.

- Topic

- Ministers Civil service

- Keywords

- Accountability Civil servants

- Publisher

- Institute for Government