Major projects in government

Major projects in government are large-scale development initiatives that aim to modernise and strengthen the UK’s infrastructure.

Major projects in government are large-scale development initiatives that aim to modernise and strengthen the UK’s infrastructure: for example, the high speed rail programme (HS2) at the Department for Transport, the biometrics programme at the Home Office, and the Ministry of Defence’s Queen Elizabeth programme to deliver two new aircraft carriers.

Major projects are overseen by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA), which manages the government’s Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP, or ‘the portfolio’) as well as providing a centre of expertise for project management in government. The GMPP encompasses ‘the most complex and strategically significant’ (not to mention ‘high-risk’) projects proposed by government departments. It contains key information about each project, including financial information, a delivery confidence assessment rating – setting out the likelihood of the project being delivered on time and on budget – and a project schedule.

Brexit-related projects, though sizeable and high priority, are not included in the GMPP. This is because of their difference in ‘scale and duration’ – Brexit projects have needed to be delivered at considerable pace, whilst GMPP projects are often in the works for years. The IPA has, however, provided support to project leads (in terms of training, planning and resources) as well as undertaking project reviews for over 100 EU Exit related projects.

What is the IPA?

The IPA is a joint unit of the Cabinet Office and Treasury, which oversees government’s major projects. It leads the way in project delivery across government departments, setting basic work standards and principles as well as providing tools and support for civil service project delivery professionals, enabling infrastructure and transformation projects to be delivered effectively and efficiently. A key part of the IPA’s role is to oversee assurance reviews at each key stage in a project’s development.

The IPA is also integral in improving government’s project delivery performance and capability over time. From 2020, the IPA is aiming to get involved earlier in project planning stages in order to improve the setting of cost and schedule estimates, which have proved troublesome for several major projects in the past few years.[1] Upskilling individuals and keeping project leaders in post is another important aspect of the IPA’s work on future improvement of governmental capability – efforts in this area include the running of a major projects leadership academy, the recruitment of specialist project delivery Fast Streamers, and the setting up of a new government projects academy. In January 2020, Nick Smallwood (chief executive of the IPA) spoke at the Institute for Government about further improvements which could be made in the government’s project delivery system.

The IPA is separate from the National Infrastructure Commission, which is a body external to government, providing expert, impartial advice on infrastructure projects.

What are the different types of major project?

In its annual report, the IPA covers four categories of project type:

- Military capability – helping to develop the UK’s armed forces so that they can maintain national security. Associated with the MoD, these projects aim to provide new equipment and technology, such as new Dreadnought submarines, as well as improvements in military systems.

- Transformation and service delivery – making the delivery of public services more efficient, and improving the experiences of users. Owned by departments across government, this category includes a wide range of projects, such as the development of a national proton beam therapy programme (DHSC) and the MoJ’s probation programme.

- Infrastructure and construction – improving and maintaining the UK’s transport, energy, sewage and water systems, as well as constructing new public buildings and helping to promote economic growth. Mostly owned by DfT, this categories includes projects such as high speed rail (HS2) and Crossrail.

- ICT – reducing costs and boosting productivity by improving or replacing government ICT systems, alongside a focus on technological innovation and digital transformation. Such projects include the Home Office’s biometrics programme and Cabinet Office’s GOV.UK Verify (the government’s digital identity verification system).

How long do major projects take to complete?

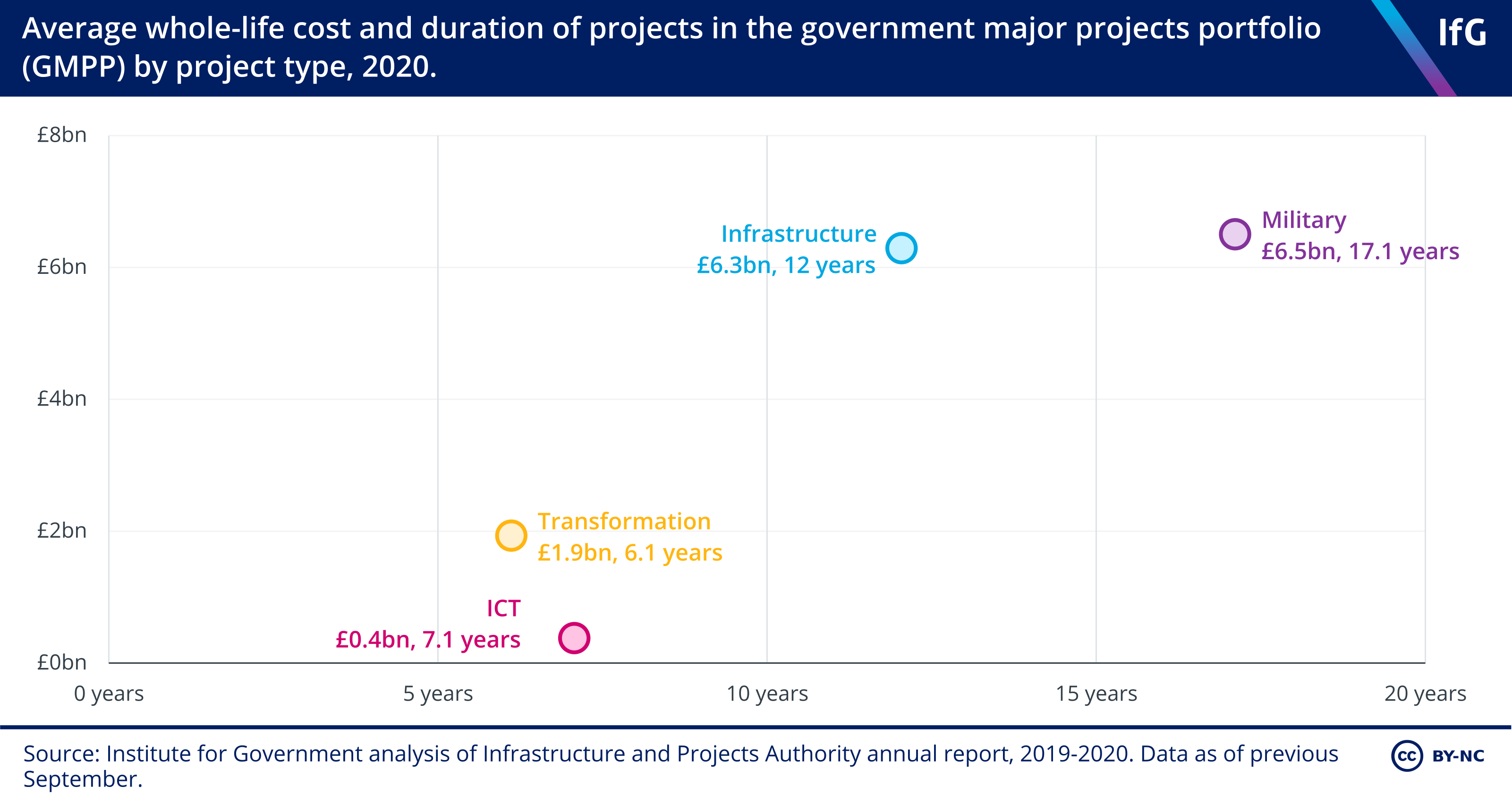

Different types of project can expect to have different completion times and costs.

Of the four categories, current GMPP military projects have the highest projected completion time – 17.1 years on average. Infrastructure projects are projected to take less time to complete – 12 years on average – but are almost as costly as those in the military category. ICT projects stand out for being the least expensive projects to run, but are estimated to take slightly longer on average (7.1 years) than the transformation projects (6.1 years) currently in the GMPP.

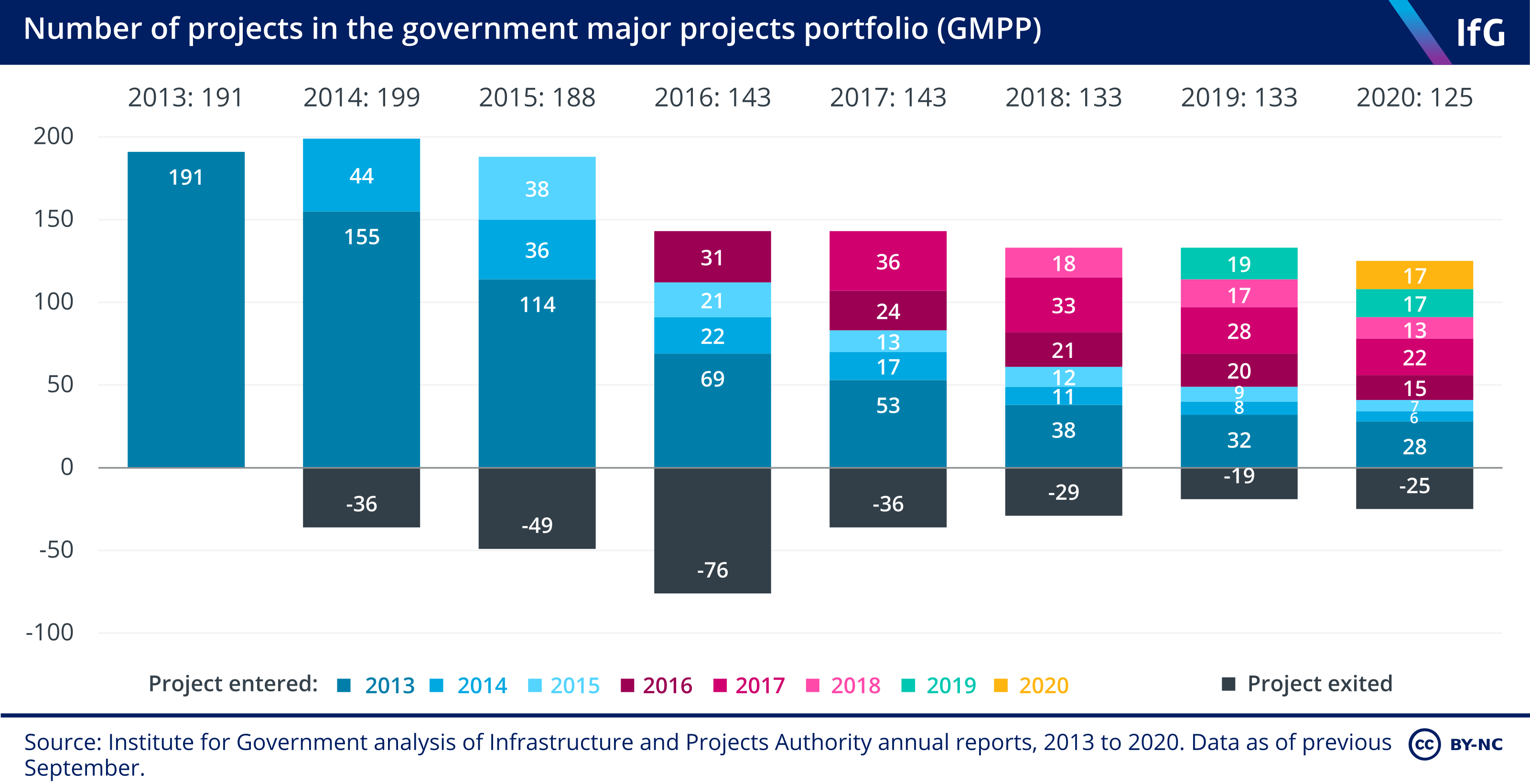

The number of major projects varies each year, as projects which have been completed or rescoped into smaller plans leave the GMPP, whilst new projects enter.

In 2019-20, 25 major projects left the portfolio. Only 17 new projects entered, leading the overall number of projects to drop to 125 – this is the smallest, in terms of number of projects, the portfolio has ever been. The number of projects reached a high of 199 in 2014, but drastically reduced in 2016 as a greater-than-usual amount of projects were due to be completed, and therefore left the portfolio.

In the 2019-20 portfolio, the two largest project categories are service transformation and infrastructure, both with 34 ongoing projects. There are 30 ongoing military capability projects, followed closely by 27 ICT and digital transformation projects.

The number of projects in the GMPP matters because it can affect the ability of the government to deliver these projects. Although the portfolio is smaller in 2020 than it has been for the last seven years, the government remains at risk of taking on more than it can deliver effectively. The Institute for Government has continually called for more effective prioritisation of government’s major projects, and others (such as John Manzoni, former chief executive of the civil service) have also stated that the civil service is doing ‘too much to do it all well’.[2] Renewed prioritisation and a focus on fewer projects might lead government teams to be able to deliver projects to the best of their ability – doing ‘fewer things really well, rather than trying to do everything in a less successful way’.[3]

Why do projects leave the GMPP?

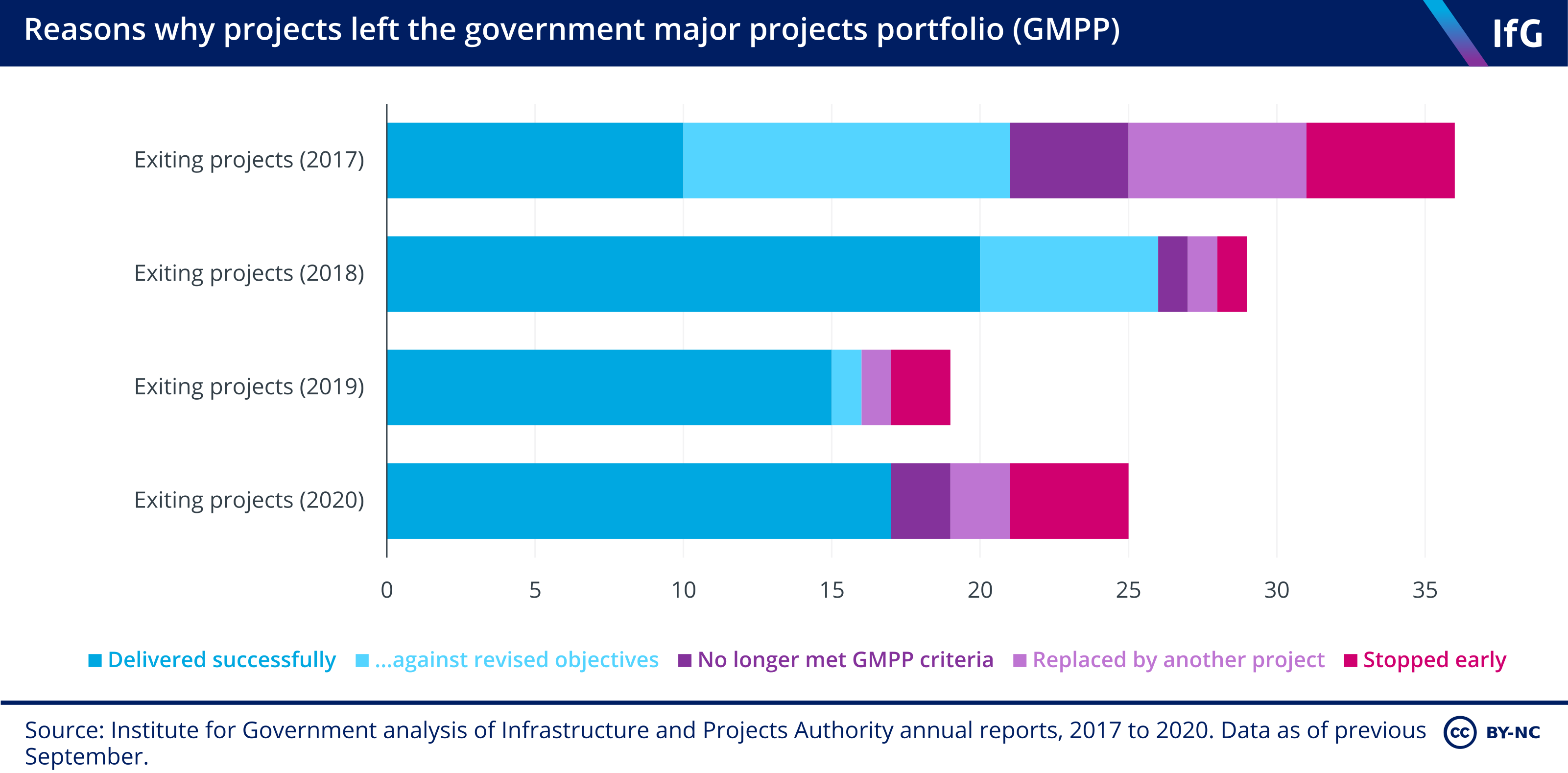

Projects leave the GMPP for various reasons. Of the 25 projects that left the portfolio in 2020, 17 were delivered successfully. Successfully completed major projects over the last few years include the expansion of superfast broadband capabilities to all parts of the UK (delivered by DCMS), the 100,000 Genomes project which sequenced genomes from patients with rare diseases and cancers (delivered by DHSC), and the implementation of a modernised logistics infrastructure for the military (delivered by the MoD).

Other projects leave the portfolio without having been completed – because they no longer meet the GMPP criteria, they have been replaced by another project, or because they were stopped early. An example of a major project which was replaced by other projects is the Prison Estate Transformation programme (MoJ), which in 2019-2020 was replaced by two smaller prison projects more focused in scope. Projects stopped early in recent years include HMRC plans to make tax digital for individuals, which were stopped due to Brexit negotiations taking priority. The digital transformation programme at the National Offender Management Service (NOMS, now HM Prisons and Probation Service) was stopped in 2018-2019 ‘as a result of re-prioritisation’.[4]

How much do major projects cost?

For each project within the GMPP, the IPA calculates ‘whole-life’ costs. These are designed to include not just immediate costs of construction and delivery, but also the planning and design costs that come at the beginning of a project, as well as the ongoing and maintenance costs that may follow after launch.

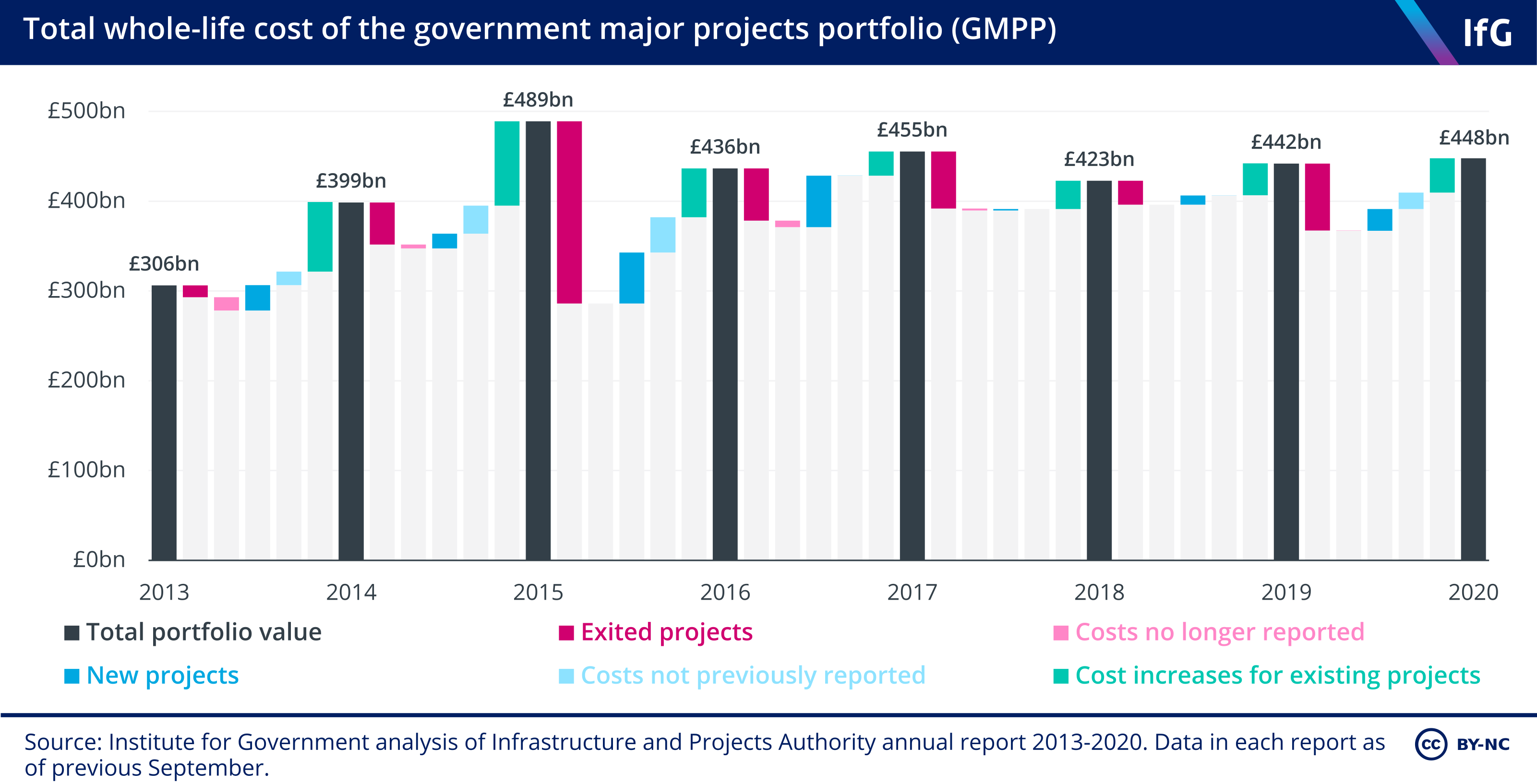

Although the number of projects in the GMPP dropped from 2019 to 2020, the overall whole-life cost of projects within the portfolio increased slightly, from £442bn to £448bn. This was primarily driven by the large increases in the costs of existing projects (£38.3bn) as well as existing projects which started reporting costs for the first time (£18.3bn). The cost of new projects entering the portfolio in 2019-2020 (£24.3bn) was relatively small, compared to the £74.6bn of projects exiting.

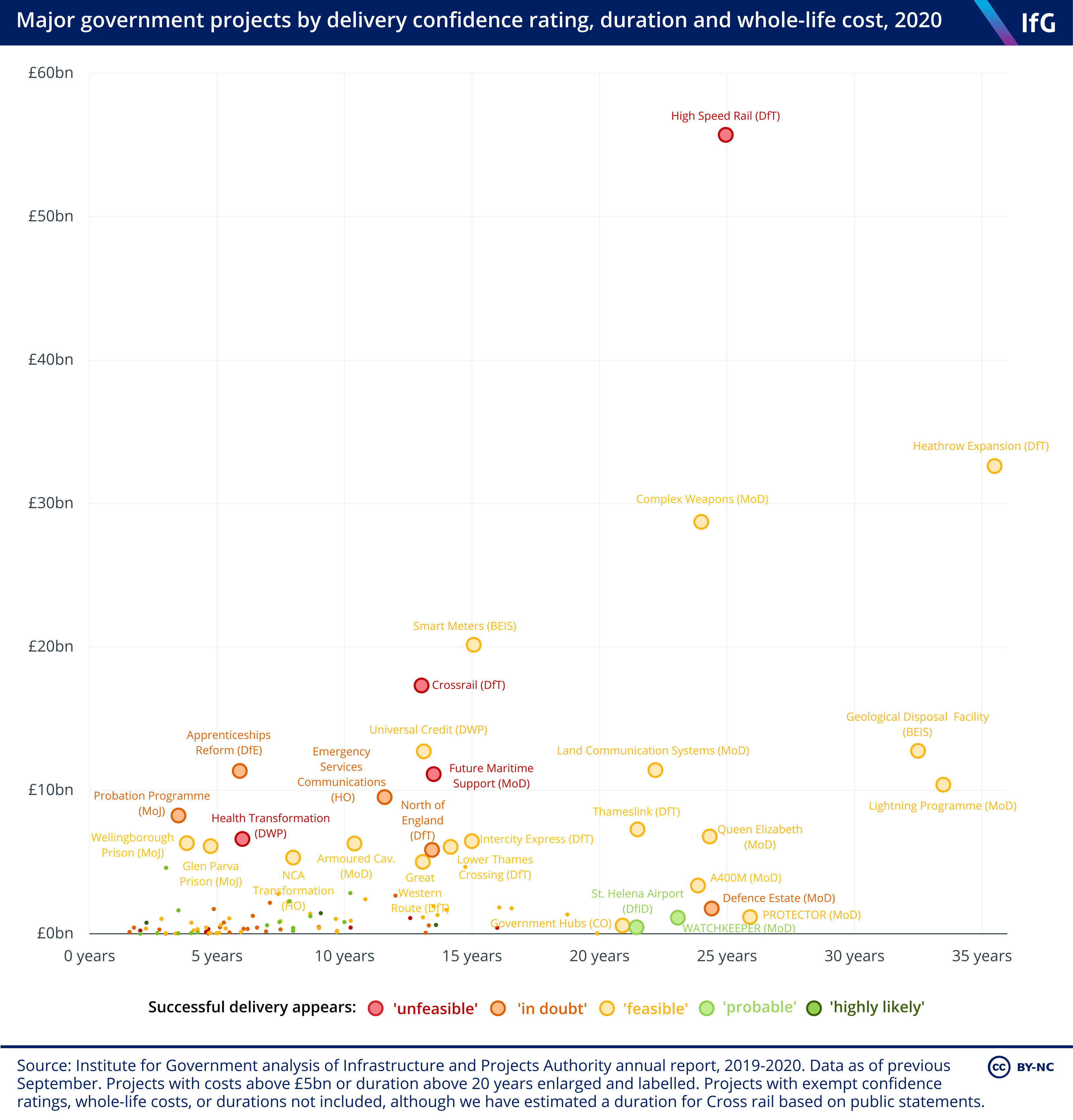

Some major projects are much costlier than others. The cheapest project in the 2019-2020 portfolio is the plan to secure a new parent body organisation for the companies in charge of decommissioning several nuclear sites and research facilities, costing around £5m. The most expensive project in the current portfolio is High Speed Rail (HS2), which has estimated whole-life costs of £55.7bn.

Current projects in the military capability category have the highest average cost, at £6.5bn. Infrastructure and construction projects are not far behind, costing an average of £6.3bn. The most expensive project in the entire portfolio, HS2, falls within this category. Transformation and service delivery projects in the 2019-2020 GMPP cost on average £1.9bn, whilst ICT projects are the cheapest by far, with an average of £0.4bn cost.

Some projects change in cost as they develop – some increase dramatically in cost, such as MoJ’s probation programme which rose in cost from £1.2bn to £8.2bn in 2019-2020 due to remodelling and the possible effects of the government’s promised 20,000 extra police officers. Other projects decrease in cost as they develop, due to changes in their outcome baselines or business cases - for example, the PHE Science Hub (DHSC) project fell from £11.6bn whole-life cost to £2.7bn during 2019 as a result of recalculations.

How are major projects spread across government departments?

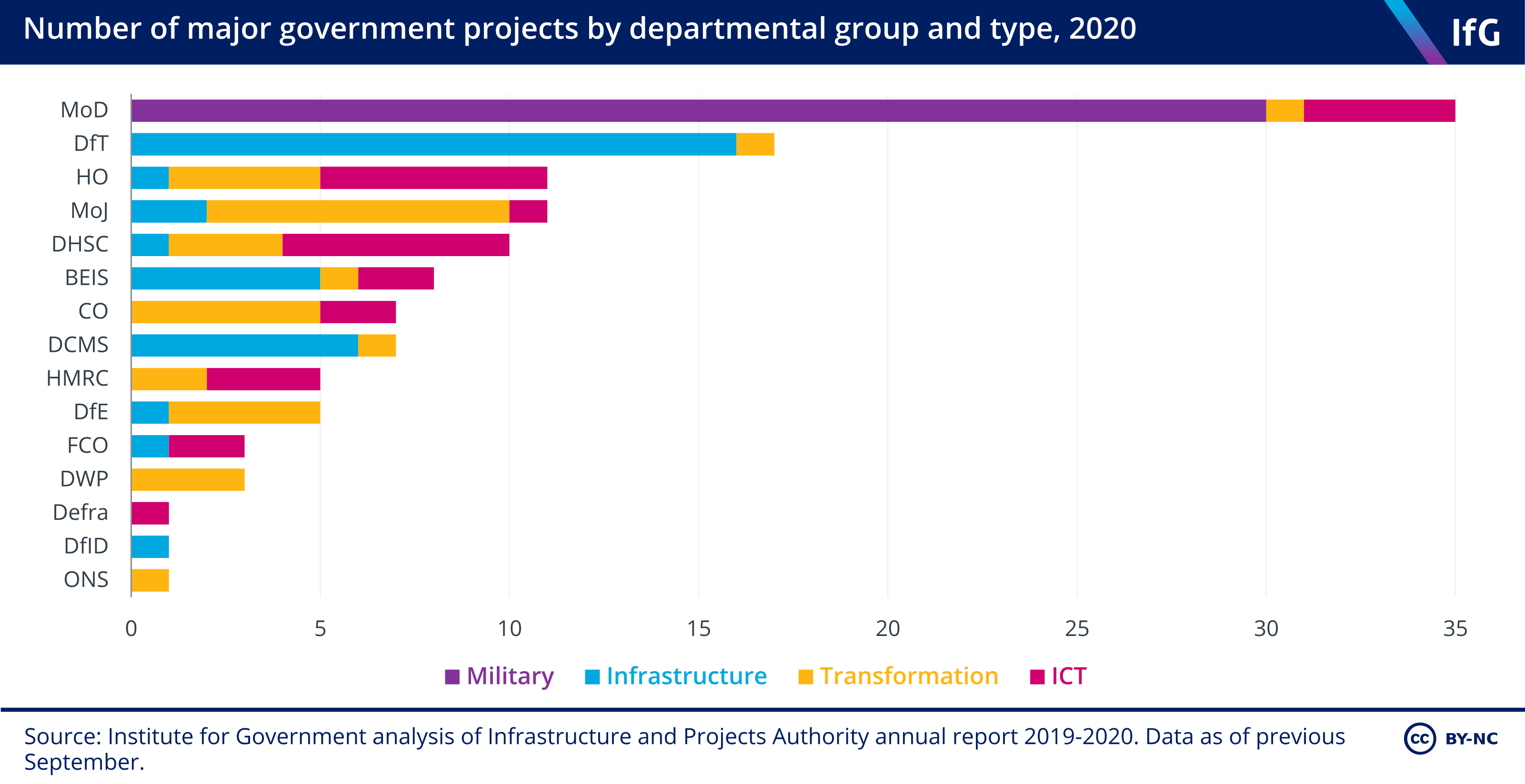

The MoD has many more major projects than any other department (35). Together, the MoD, DfT (with 17 projects) and HO (with 11) oversee more than half of the projects in the 2019-2020 portfolio.

The MoD is responsible for all 30 military capability projects, while most infrastructure and construction projects are run by DfT (e.g. HS2) or BEIS (e.g. Smart Metering Implementation Programme). ICT and transformational service delivery projects are spread more evenly across departments, with a particularly large number of projects at the HO, DHSC and MoJ, which have large service delivery functions.

Not all departments have major projects. The IPA did not oversee any major projects in 2019-2020 managed by the Treasury (HMT), the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) or the Department for International Trade (DIT).

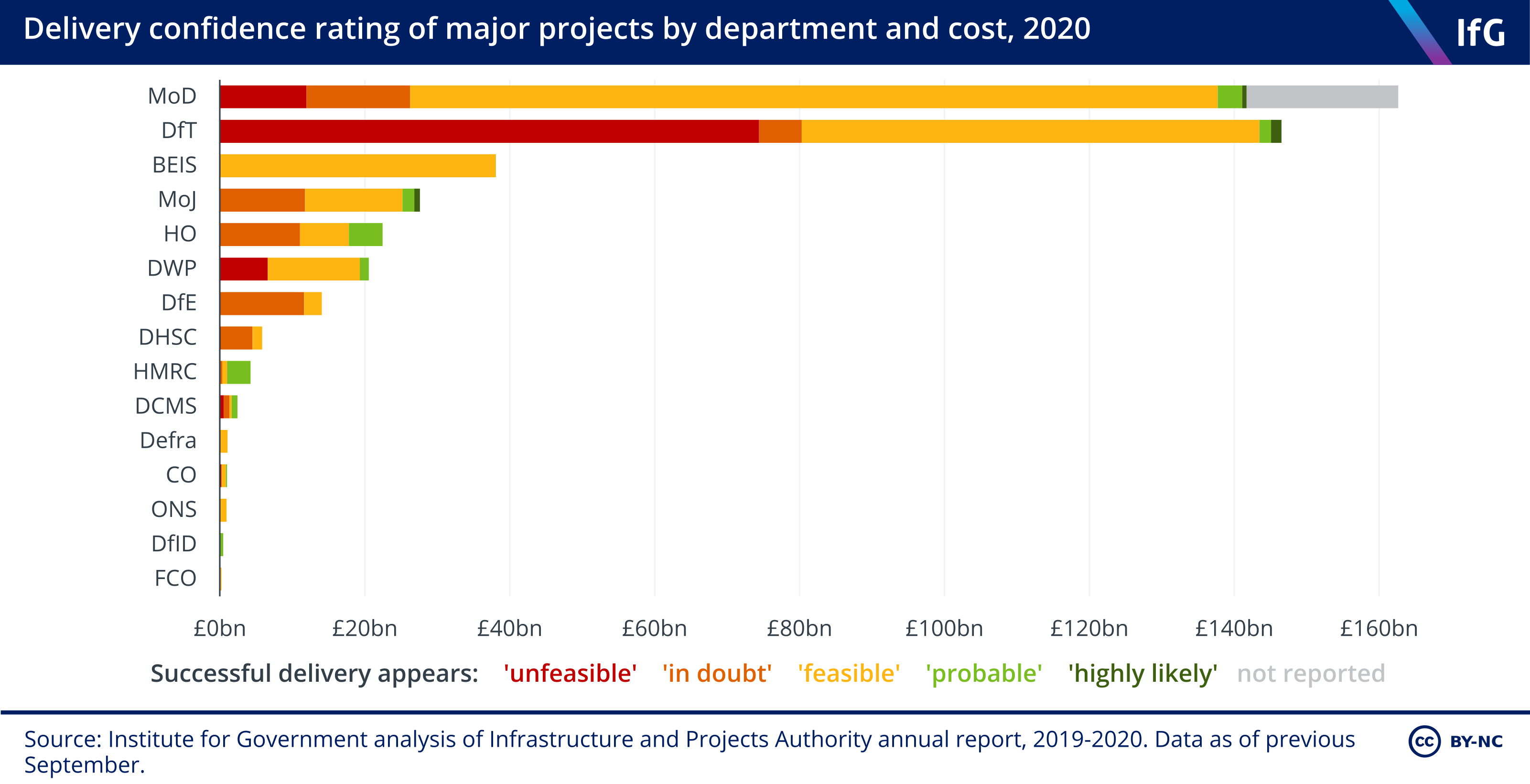

Together, the whole-life costs of the projects overseen by MoD and DfT account for £310bn, which is almost 70% overall cost of the GMPP. Despite the HO, MoJ and DHSC being responsible for more individual projects than BEIS, their overall costs are lower. This is because they focus mostly on ICT and transformational service delivery projects, which tend to be much cheaper than the many infrastructure projects overseen by BEIS.

The whole-life costs of projects across departments judged by the IPA to be ‘unfeasible’ when it comes to delivering on time and on budget add up to almost £94bn. The whole-life costs of projects given a ‘highly likely’ delivery confidence ratings by the IPA in 2020 add up to less than £3bn.

How well is the government delivering its major projects?

In its annual reports, the IPA assesses the likelihood that major projects in the GMPP will achieve their objectives on time and on budget. Each project is given a red/amber/green (RAG) delivery confidence rating:

- Green – successful delivery appears highly likely.

- Amber/green – successful delivery appears probable, but attention is needed to prevent risks becoming major problems.

- Amber – successful delivery appears feasible, but significant issues already exist.

- Amber/red – successful delivery is in doubt.

- Red – successful delivery appears unachievable.

Rating reset – significant changes to project baseline, with business case being refreshed or changed.

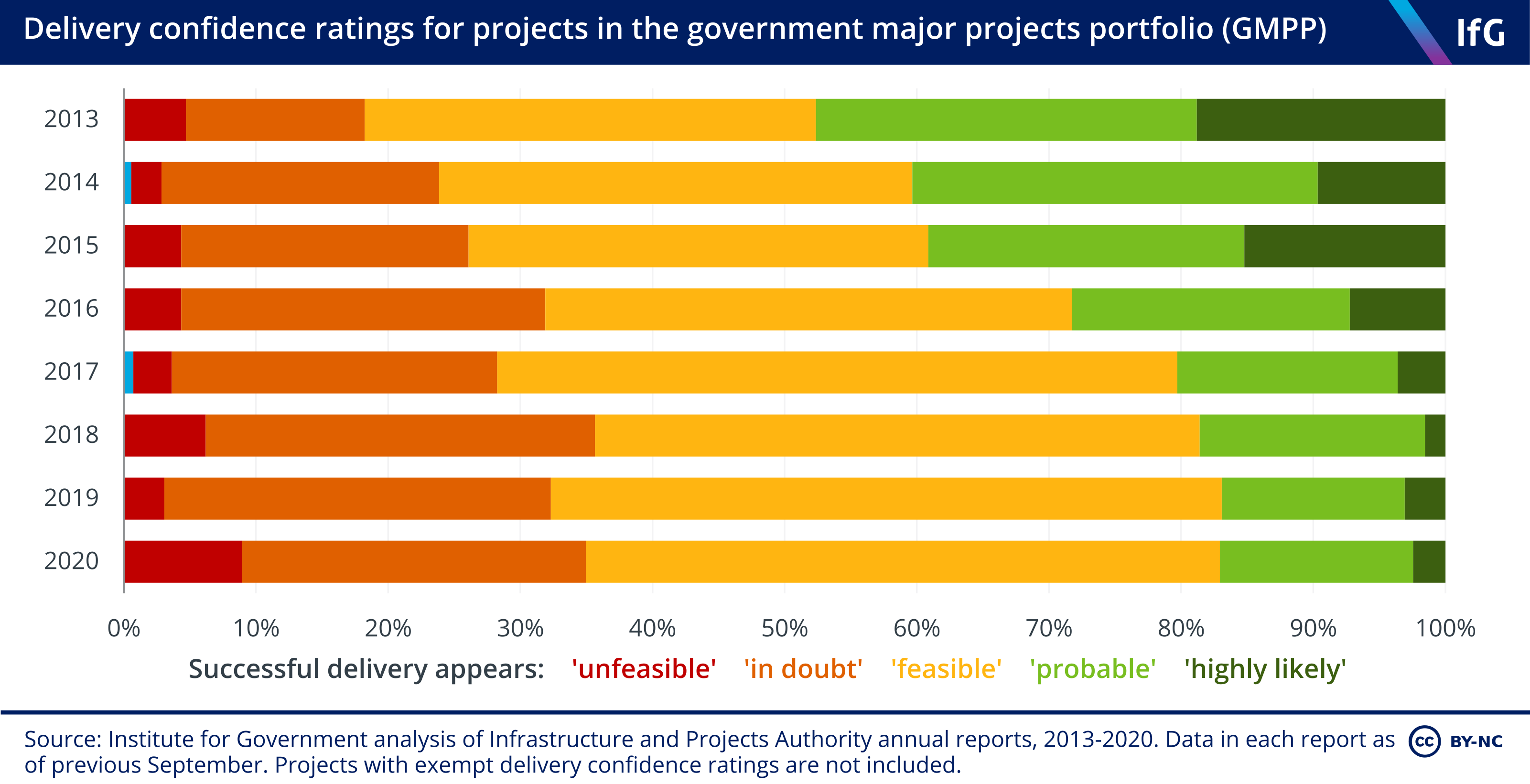

The IPA’s overall confidence about the delivery of projects within the portfolio has been falling steadily since 2013. In 2020, 11 projects in the GMPP (9%) were considered to be ‘unfeasible’ in their delivery, the worst possible delivery confidence rating applied by the IPA. This is a record high, and represents a six percentage point increase on 2019. Some of the most high profile portfolio projects fall into this rating category, such as high speed rail (HS2) (DfT), Crossrail (DfT) and GOV.UK Verify (CO).

In 2020, only three of the 123 GMPP projects with known delivery confidence ratings (2%) were considered ‘highly likely’ to be delivered on time and on budget. This is a slight fall from 2019, although the proportion of projects considered ‘probable’ or ‘highly likely’ to succeed has remained at a steady 17%.

Projects in the current portfolio with a ‘highly likely’ delivery confidence rating include the prison education programme (MoJ) which aims to provide education services for adult prisons in England, and the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme (DfT).

The delivery confidence ratings given to major government projects in each IPA annual report often change each year as projects progress. From 2019 to 2020, 28 of the existing major projects (27%) which have publicly available delivery confidence ratings saw their ratings improve, while 23 existing projects (22%) saw their delivery confidence ratings fall – this includes high speed rail (HS2). This is a slight increase on 2018-2019, when only 17% of projects saw their ratings fall. The majority of existing major projects (54, or 51%) had their rating remain the same in 2020 as in the previous annual report.

The trend of increasing levels of risk is driven in part by the IPA’s focus on the hardest, most challenging and complex projects the government is undertaking. Projects tend to see their confidence delivery ratings improve while in the portfolio, and those exiting the portfolio after successful delivery tend to have the best ratings. There is thus the risk that longer term, riskier projects accumulate in the portfolio, bringing down the average IPA confidence in government’s major projects.

Are certain kinds of projects more likely to be given higher confidence ratings?

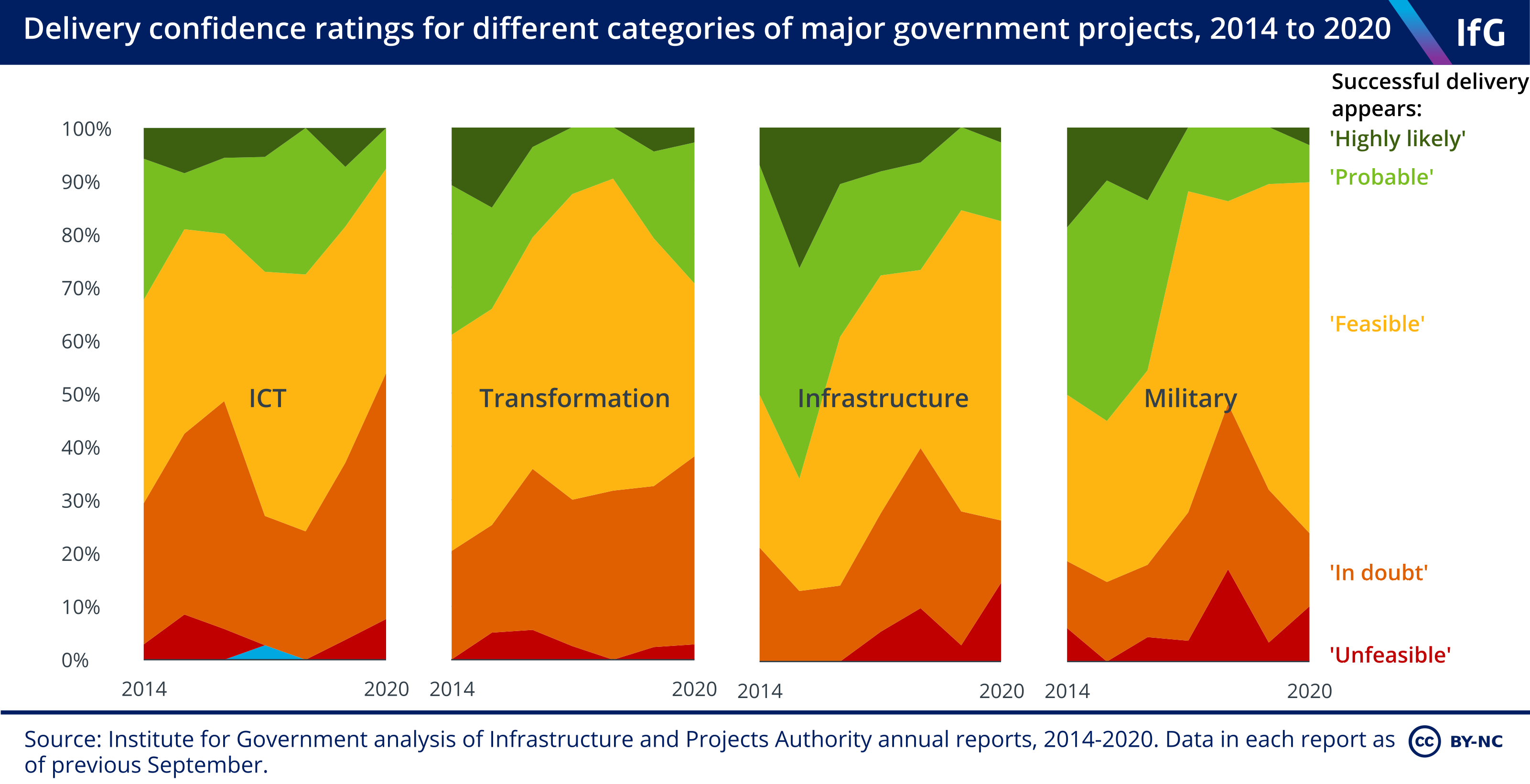

In 2020, GMPP projects within the service transformation category were most likely to be rated as ‘highly likely’ or ‘probable’ (29%). The ICT and digital transformation category had the highest proportion of projects rated ‘unfeasible’ or ‘in doubt’ (53%) which is a record high – no ICT projects were rated ‘highly likely’, which is a drop from 7% in 2019.

An increasing number of infrastructure and military projects were rated as ‘feasible’ in 2020 – this is a reversal of the trend of the previous six years, where these types of projects were consistently more likely to be judged as at risk. The Maritime Sustainment Programme (MoD), which aims to replace Royal Fleet Auxiliary tankers, is the first major military capability project rated ‘highly likely’ to succeed since 2017.

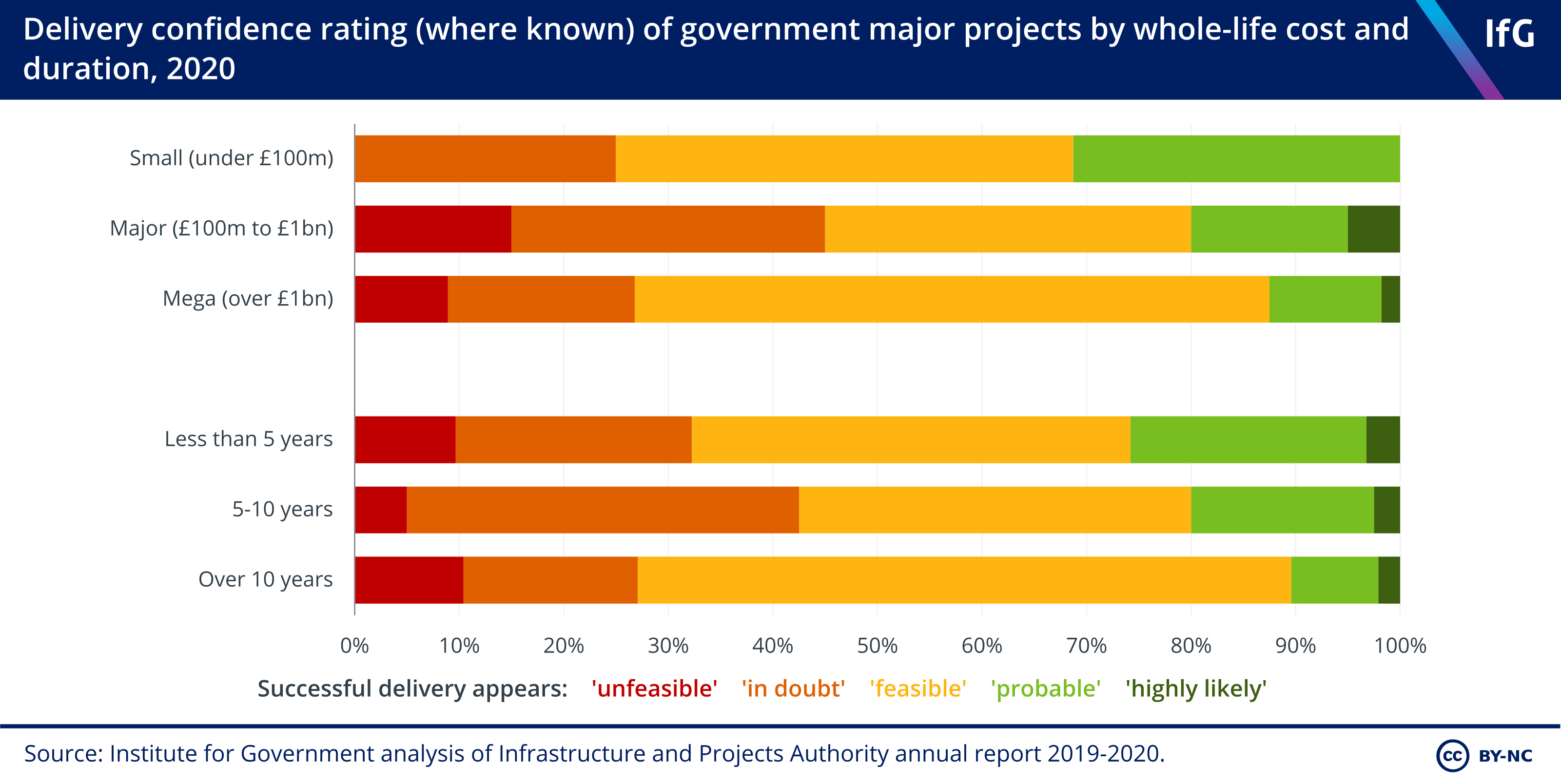

Within the 2020 IPA annual report, longer and more expensive major projects tended to be less likely to have a ‘probable’ or ‘highly likely’ confidence delivery rating. However, more expensive and lengthy projects were not necessarily more likely to be judged as ‘unfeasible’ or ‘in doubt’. This has been the trend over the past few years, where larger major projects have not been deemed inherently riskier at the outset than shorter or cheaper ones. Each project has its own unique set of circumstances and issues – just because a project is larger doesn’t necessarily mean it is riskier, and with strong, consistent leadership, length or high cost should be no barrier to successful project completion. The trend which has emerged in this year’s portfolio is thus likely to change again in future.

How have specific projects changed over the last year?

Costs, timelines and confidence ratings for major projects can change each year. Key changes in the 2020 IPA annual GMPP report from the previous year include:

- High speed rail (HS2) (DfT) had its delivery confidence rating downgraded to ‘unfeasible’ for the first time. Whole-life cost and schedule estimates (£55.7bn and 25 years) remain constant.

- Heathrow expansion programme (DfT) whole-life cost estimates increased from £22bn to £32bn, and its delivery timeline was lengthened by 21 years. The estimated date of delivery has been moved from 2029 to 2050. Its IPA delivery confidence rating remains at ‘feasible’.

- Crossrail (DfT) whole-life costs increased from £15.5bn to £17.6bn. The project’s IPA delivery confidence rating remains ‘unfeasible’, to which it was first downgraded in 2019.

- Probation programme (MoJ) whole-life cost estimates increased from under £1bn to around £8bn, and its delivery confidence rating remains ‘in doubt’.

- Projects which saw their delivery confidence rating improve include the Health and Social Care Network (DHSC – upgraded from ‘in doubt’ to ‘feasible’), the St Helena airport project (DfID – upgraded from ‘feasible’ to ‘probable’), and the Making Tax Digital for Business programme (HMRC – upgraded from ‘in doubt’ to ‘probable’).

- Infrastructure and Projects Authority annual report 2018-2019, page 30, www.gov.uk/government/publications/infrastructure-and-projects-authority-annual-report-2019

- Whitehall Monitor 2020, page 58, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/whitehall-monitor-2020; John Manzoni in Suzannah Brecknell, “Civil service leaders must re-prioritise for Brexit, says chief John Manzoni”, Civil Service World, 9 November 2016, www.civilserviceworld.com/articles/news/civil-service-leaders-must-re-prioritise-brexit-says-chief-john-manzoni

- Matthew Vickerstaff, “Speech: Making Project Delivery and our System Fit for the Future”, Infrastructure and Projects Authority, GOV.UK, 16 January 2019, retrieved 26 June 2020, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/making-project-delivery-and-our-system-fit-for-the-future; Richard Johnstone, “Projecting forward: IPA chief Tony Meggs on how to improve delivery of government’s biggest schemes”, Civil Service World, 17 September 2018, retrieved 26 June 2020, www.civilserviceworld.com/articles/interview/projecting-forward-ipa-chief-tony-meggs-how-improve-delivery-governments-biggest

- Infrastructure and Projects Authority, Annual Report on Major Projects, 2018-2019, GOV.UK, 18 July 2019, retrieved 29 June 2020, page 10, www.gov.uk/government/publications/infrastructure-and-projects-authority-annual-report-2019

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- High Speed 2

- Publisher

- Institute for Government