What have we learned so far from the English devo deals process?

And what are the challenges ahead?

English devolution is currently high on the agenda, as part of the Government’s drive to deliver a ‘smarter state’. Jo Casebourne and Joe Randall take a look at the 'devo deals' process so far, and the challenges ahead.

One of the key themes of the Prime Minister’s recent ‘smarter state’ speech was English devolution, and the transfer of power via a series of devolution deals between the Treasury and local areas. In the July Budget, local areas were invited to submit their proposals for new devolution deals with the Government. After a hurried seven-week process, 38 submissions were received by the 4 September deadline, well above the 25 the Government expected. So the attempt to put the pressure on and galvanise local areas certainly worked. Today the Chancellor announced the first of this batch of deals, with Sheffield City Region. But what have we learned from the process so far?

The pitfalls of doing complicated devolution at breakneck speed

The negotiations between cities or counties and Whitehall are occurring in a vacuum, in which local areas don’t understand what they can and can’t bid for. The centre is deliberately not articulating a vision for what they think devolution can achieve, as that is seen by ministers as going against the grain of a deal process that must start with what local areas want. But if Whitehall had clarified which, if any, programmes or policy areas were ‘off the table’ in advance, it would have avoided wasting the precious time and effort of local areas asking for devolution in policy areas that they were never going to get. For example, the that the Government will not negotiate on devolution of the National Careers Service or the Work Programme.

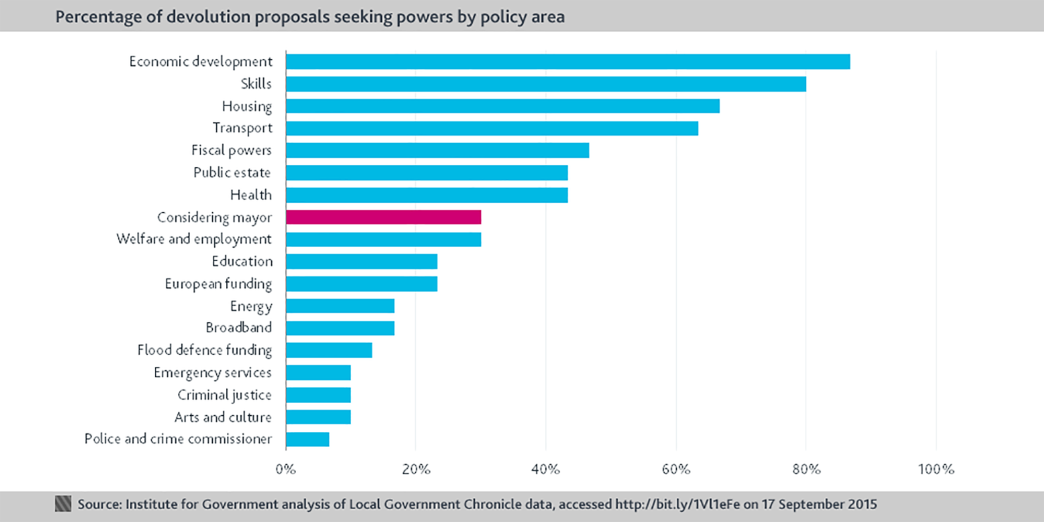

This graph shows what 30 of the 38 submissions are asking for:

The original focus on local economic growth and infrastructure of much of pre-election decentralisation remains, but it’s interesting to also see submissions asking for devolution of public services. Eighty percent of submissions are asking for skills devolution, while policy areas like health and education also feature quite strongly. But how are the bids going to be assessed? The process and criteria for doing so (with the exception of the Government wanting to see more metropolitan mayors) is opaque.

It’s also perhaps not that surprising that there are some rather curious deal boundaries emerging, when areas had to conduct internal discussions and negotiations with other areas when many key players will have been on holiday. Even without it being Summer, seven weeks would not have been long to establish meaningful partnerships where none had existed before. It’s also not long enough to do the serious planning necessary to think through how these deals will be implemented if successful.

Four challenges ahead for Whitehall

Our past work has shown that decentralisation is hard to do. Just as in devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, in the English devolution context Whitehall needs to recognise and prepare for the challenges of operating in a more fragmented landscape and to consider the accountability and failure structures needed, and the cooperative shared-power models that will be necessary. We see four key challenges ahead for central government:

- Adopt a more principles-driven approach. If English devolution is to achieve the desired outcomes of local growth and better public services, Whitehall needs to do some serious thinking and planning about the distribution of powers and funding, structures and relationships. To avoid the whole process feeling like favouritism, local areas need to understand the criteria used in negotiations, so there is clear reasoning behind who eventually gets what.

- Keep the Treasury involved after the Spending Review. HM Treasury involvement in driving the deal-making is not enough. Pre- and post-Spending Review settlements are the start of the process, not the end and the Treasury needs to stay involved in the implementation phase, or agreements risk becoming watered down and ineffective. Without a powerful champion for the deals process, departments will be able to row back on the pledges that are made when an ‘in principle’ agreement is signed.

- Join up devolution across Whitehall. Central government needs to have clear relations with cities rather than muddling through. Since the abolition of the government offices of the regions, central government’s relations with cities are more loosely organised, and it needs to rethink how those relationships are managed if devolution is to be sustainable, and the benefits of local experimentation and innovation are to be realised. English Civil Service departments also need to make connections with the other UK nations and the national devolution processes, to learn lessons about the challenges ahead within England.

- Develop cooperative models. City-level devolution will inevitably be messier than national devolution, with a far greater number of overlapping competences and ‘jagged edges’ in policy areas owned by both central and local government. Government at all levels needs to think through the cooperative shared-power models that will be necessary to operate in this environment, while maintaining clarity on who controls what.

- Topic

- Devolution Public finances

- Administration

- Cameron government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government