The Hansard Society has published its latest Audit of Political Engagement, its ‘annual health check on public attitudes to our democracy’. But can it tell us anything about public attitudes to the effectiveness of government?

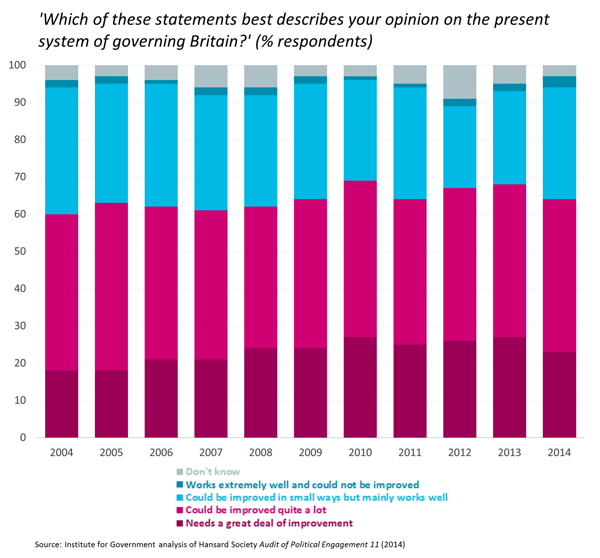

The Hansard Society’s Audit of Political Engagement is one of our most valuable sources on public attitudes towards politics. This year’s Audit, published at the end of April, is full of interesting findings, from 49% of people being certain to vote in a General Election tomorrow (up from 41% last year but still the third lowest since the series began in 2004) to 74% saying that ‘politicians should be prepared to make personal sacrifices if they want to play a role in running the country’, described at the report’s launch by Lord Bew as an ‘emotional tax’. The nearest thing Audit 2014 has to a question on government effectiveness – or, rather, perceptions of government effectiveness – is: ‘Which of these statements best describes your opinion on the present system of governing Britain?’ Respondents were given four options: • ‘Needs a great deal of improvement’ • ‘Could be improved quite a lot’ • ‘Could be improved in small ways but mainly works well’ • ‘Works extremely well and could not be improved’.

- Publisher

- Institute for Government