Regression analysis: the pipeline of women leaders in Whitehall is badly blocked

The announcement that Alex Chisholm has been appointed to head of the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) completes the most recent round of permanent secretary appointments. It makes the top leadership of the Civil Service less diverse than it has been for several years. Jill Rutter and Leah Owen look at what has happened.

Sir Jeremy Heywood, Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Civil Service, has declared his commitment to diversity. He has appointed a high-level group of diversity advisers, and commissioned a report on the blockages in the pipeline of female talent. And he has explicit objectives on promoting diversity at senior levels in his personal objectives.

That is why it is surprising that he has presided over a decline in diversity at the top of the Civil Service of epic dimensions.

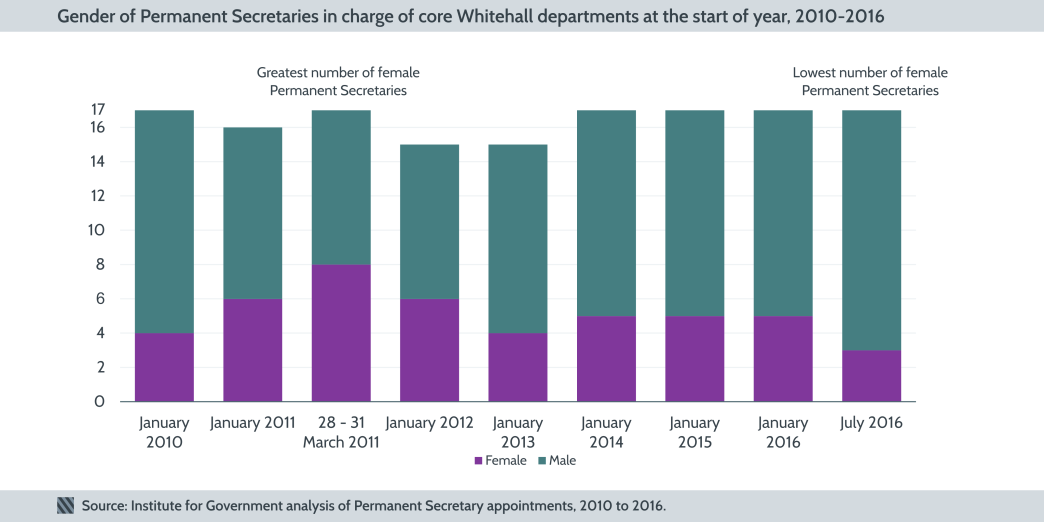

In May 2010, four women were in charge of Whitehall departments. That reached eight for a brief half week in March 2011. Now there are just three – plus a woman permanent secretary heading the Government in female-friendly Scotland.

In the last round of permanent secretary appointments, two women and one man stepped down: Lin Homer at HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC), Una O’Brien at the Department of Health (DH), and the incredibly long-serving Nick Macpherson at HM Treasury (HMT). They were all replaced by men – two in managed moves, while Tom Scholar was victor in a two-man race to run the Treasury. Jon Thompson at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) was then replaced by the former DECC Permanent Secretary, Stephen Lovegrove. The two vacancies at the Department for Education (DfE) and DECC have just gone to men. Six opportunities to find a woman, but none found – and, of course, none of the appointees are BME (black and minority ethnic) or disabled.

So how has this happened? Hopefully this is the question at the top of the Cabinet Secretary’s in-tray. Here are some thoughts:

Did women not apply? It’s hard to say from outside. All-male shortlists are supposed to be the exception. But of course for managed moves, it’s just a tap on the shoulder – and in the Cabinet Secretary’s discretion, whose shoulder to tap. And if well-qualified women are deciding not to apply, what does that say about their perception of these top jobs?

Did women apply but not get selected by the panels? Here it is interesting to see how the competitions were run. If you want to promote diversity at the top level, it is easier if you give yourself a slate of appointments to make, rather than run individual competitions – where you discover that for each job you appoint a man and suddenly end up missing your diversity objectives. The three competed jobs – HMT, DfE and DECC – were run one after another.

Is it ministers’ fault? The Prime Minister now has a new role in choosing from suitable candidates put forward by panels.

Are more men coming through the pipeline of talent? In which case, what has happened to all the hard work since the early 2000s to improve the number of women getting into director-general roles and being given the encouragement and opportunities to compete for the top jobs?

More importantly still – what does the Cabinet Secretary propose to do next to signal to women that they can still aspire to the top jobs? As the IfG’s study on the history of women in Whitehall has shown, Whitehall is better than other employers for appointing women – but has had a long history of women struggling to break through that top barrier.

Whitehall has a long history of diversity initiatives. Today’s diversity champions and the inclusion of diversity goals in permanent secretary objectives all speak to the seriousness with which Whitehall supposedly takes this issue. Yet it has also had long problems with culture, and with promotion in one’s own image. There is often a mismatch between the kind of leaders Whitehall says it wants and the ones who actually get the job.

This may seem just a few posts, to be filled purely on skills and competency, and which should not be taken as representative of Whitehall’s commitment to diversity. But for those civil servants who don’t fit the mould of the appointments just made, it speaks volumes about whether they are really part of the future of Whitehall.

- Topic

- Brexit