Oliver Ilott argues that George Osborne has made life more difficult for himself in the upcoming Budget, by failing to get a grip on £117bn-worth of tax expenditures.

Tax expenditures are tax discounts or exemptions that further the policy aims of government. They cover everything from the zero rate of VAT on children’s clothes to inheritance tax relief. As he contemplates this week’s Budget, the Chancellor may be regretting that hasn’t developed a method for considering the effectiveness of tax expenditures, and potentially finding savings.

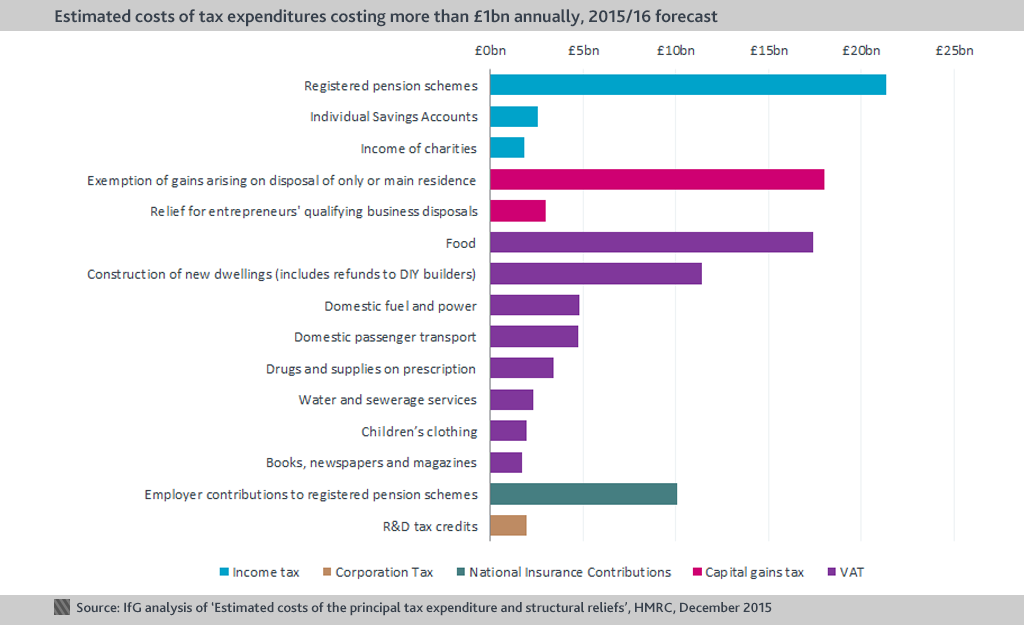

With pre-election pledges limiting his options for reducing general expenditure, or raising revenue through tax rate changes, the Chancellor could do with a third front. The chart below depicts those tax expenditures costing more than £1bn annually and reveals one of the reasons why tax expenditures might not get the attention they deserve: they often relate to politically sensitive issues.

The attempt (abandoned last week) to reform pension tax relief was a sign that the Chancellor is willing to consider ways of raising revenue by curtailing tax expenditures, despite this political sensitivity. But the haphazard way in which the reform was developed: without substantive consultation, leaked to the press and then dropped in the week before the Budget, speaks to a lack of established process within the Treasury for this type of reform.

If the Chancellor wants to get serious about tax expenditures, for this or any future budget, he should:

1. Accept (even embrace) transparency.

At present, many tax breaks have no official estimate of cost, making it impossible for the public or policymakers to assess their value. When the National Audit Office (NAO) examined tax expenditures, the Treasury responded by disputing the organisation’s jurisdiction, claiming that “the design and impact of a relief are questions of policy and therefore outside of the NAO’s remit.” This seems needlessly evasive.

The Treasury should publish the cost/benefit analyses for each of its tax expenditures and invite organisations such as the NAO to audit them.

2. Introduce a systematic review of tax expenditures into the budget process.

As the NAO found, the Treasury does not control tax expenditures with the same rigour as it does general expenditure – for example, the cost of entrepreneur’s relief has repeatedly exceeded forecasts, rising by over 500% since it was introduced in 2008/09. At present, tax expenditures are not included in the Treasury’s own budget-formation process and therefore are not subject to appropriate levels of scrutiny.

3. Subject tax expenditures to the same test as other policy options.

Once the Treasury has begun to take a closer look at tax expenditures, they should start to ask themselves whether these are the most effective tools for delivering a given policy aim. My colleague Jill Rutter makes the case that the technical argument for a zero rate of tax on children’s clothing would not survive any serious comparison with other Department for Work and Pensions, or Department for Education, expenditure.

Tax expenditures can be a useful arm of policy, but they should be subject to a fundamental test: if this were a departmental spending programme, would it survive? In pursuing these reforms, the Chancellor may come up against a Treasury machine for which the special status of tax expenditures has become a habit. But as demonstrated by the independence of the Bank of England or the formation of the Office for Budget Responsibility, Treasury norms can be broken when the political will is strong enough.

For a Chancellor trying to balance spending against revenue, it is clear that tax expenditures need to be part of the fiscal equation.

- Topic

- Policy making Brexit