After uncertainty in the run up to the election, continuity characterises the post-election landscape in Whitehall: Cameron’s cabinet looks much the same as it did before. But is the same true of the rest of the government? Emily Andrews crunches the numbers.

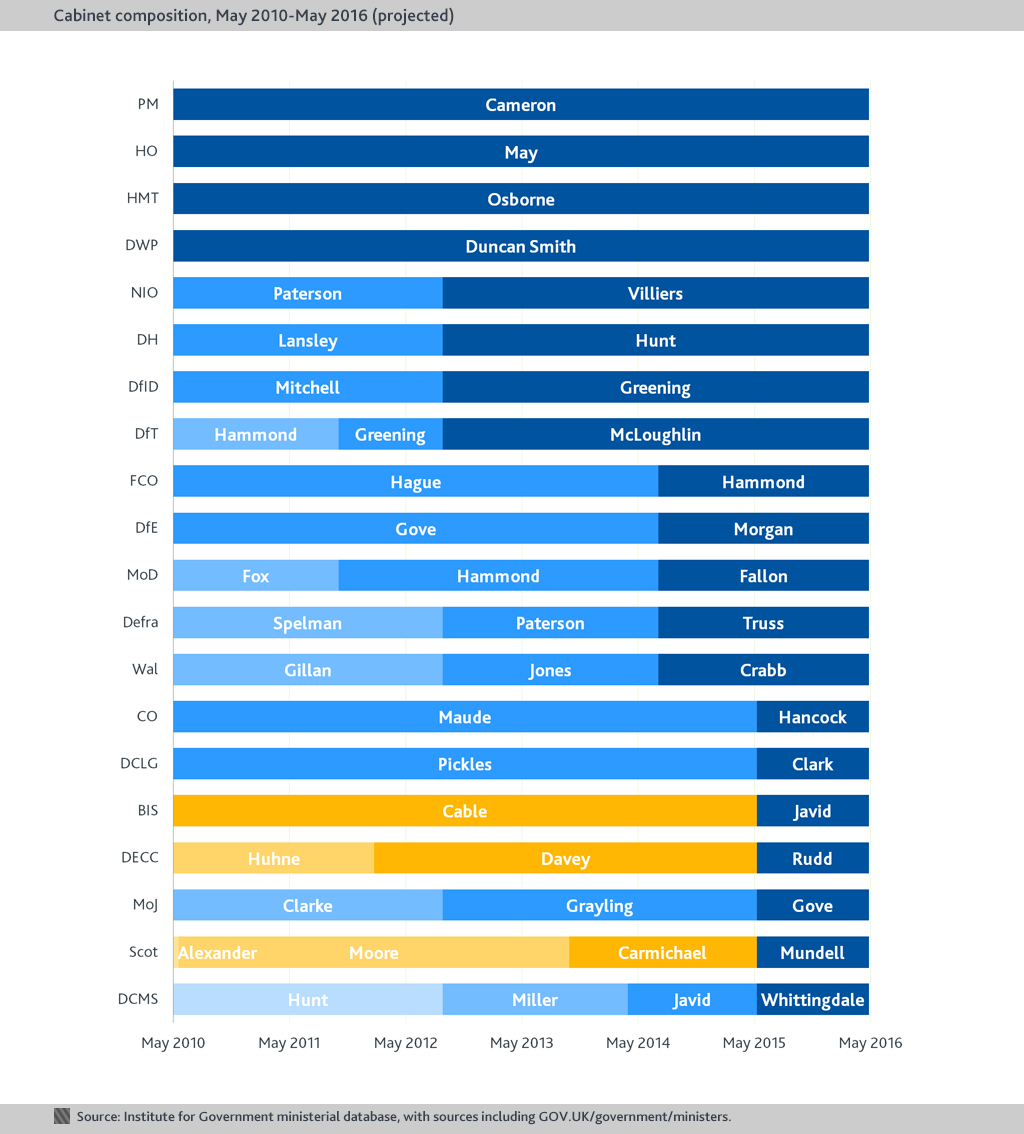

In addition to No 10, 12 out of 19 departments are headed by the same minister.

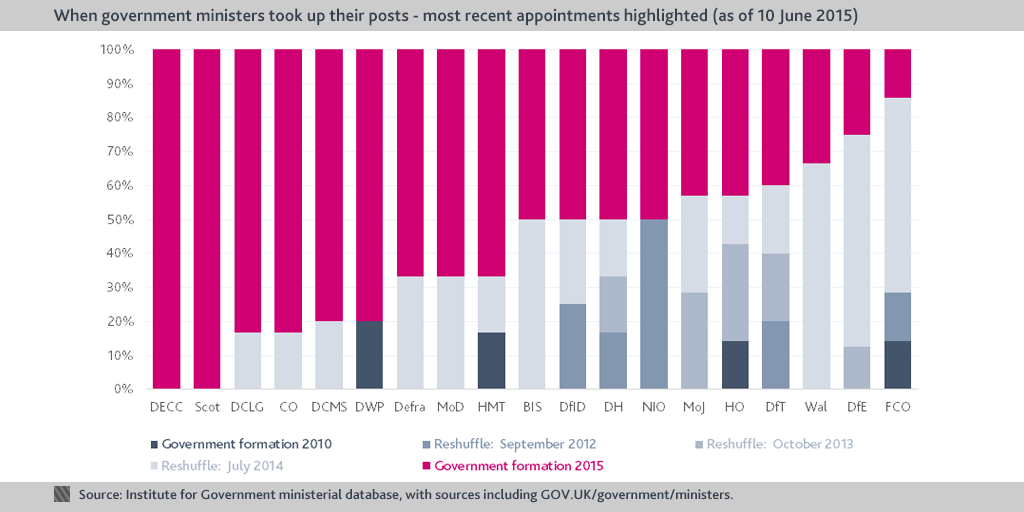

- There are eight departments where over half the ministerial team are new to their job (DECC, Scotland, DCLG, CO, DCMS, DWP, MoD, HMT).

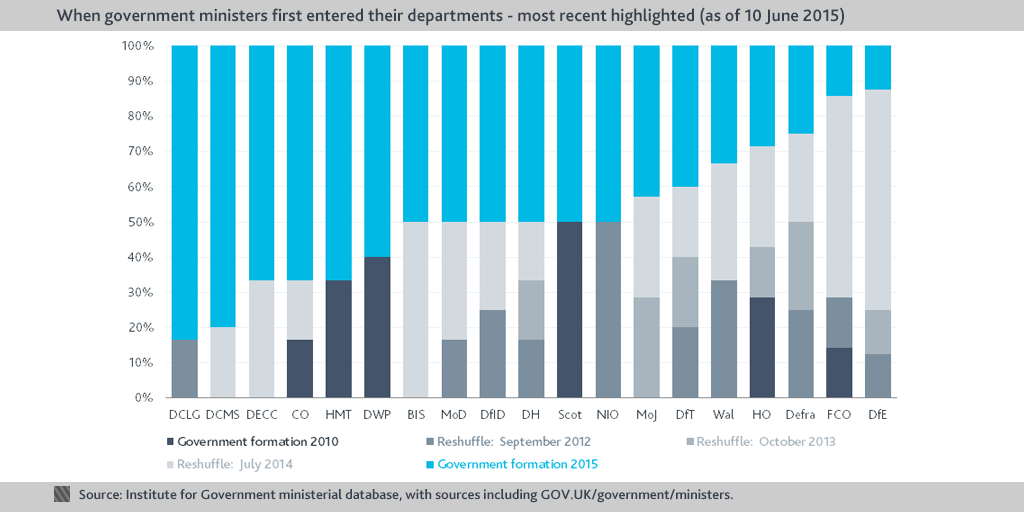

- Conversely, there are six departments where over half the ministers are in the same post as before the election.

- The two departments where all the ministers are new to their jobs – DECC and the Scotland Office – also have two of the smallest ministerial teams in Whitehall (DECC has three ministers, and Scotland only two). However, in both cases the new secretary of state was formerly a junior minister in the same department.

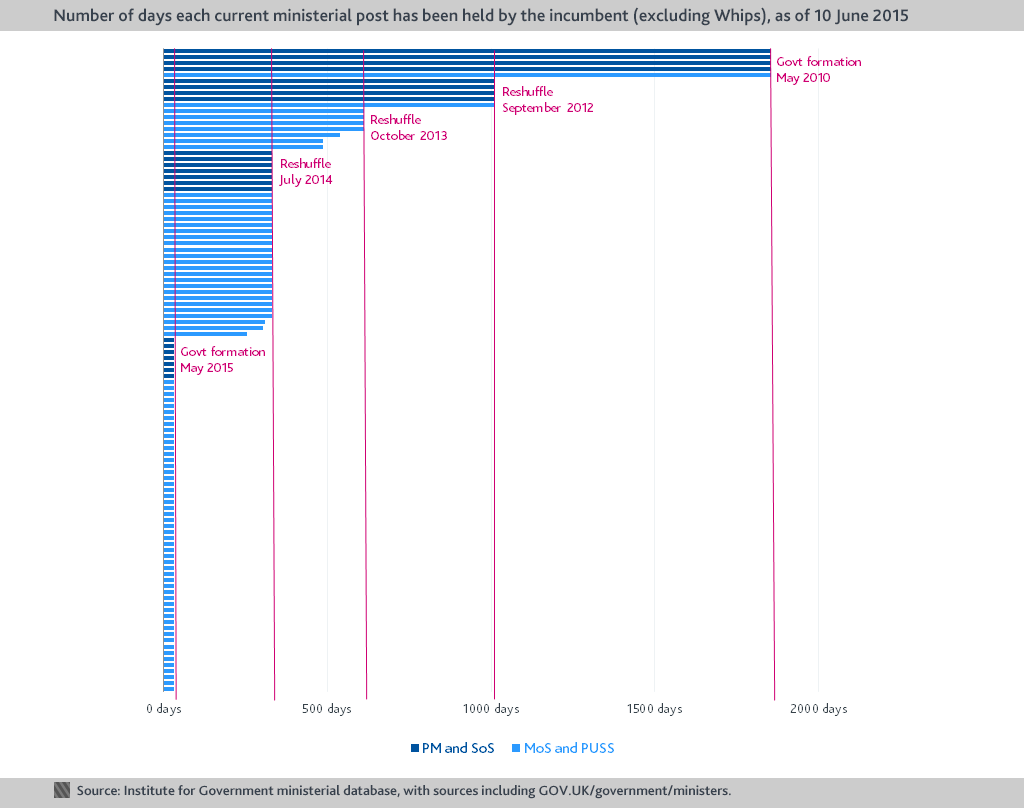

- Only four departments (DWP, HMT, HO and FCO) have a minister who has held the same post since 2010: all but one of them is a secretary of state.

- FCO, DfE and the Wales Office have seen the most continuity in the post-election reshuffle. But in all of those departments, most of their ministers have been in their job for less than a year.

…but not all of them are new to the department.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Cabinet Government reshuffle

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government

- Public figures

- David Cameron

- Publisher

- Institute for Government