On Saturday 7 March, Radical Statistics held their annual conference on the subject, ‘Good Data, Good Policy?’ Gavin Freeguard was asked what could be done to improve the current situation – he gives a summary of his contribution below.

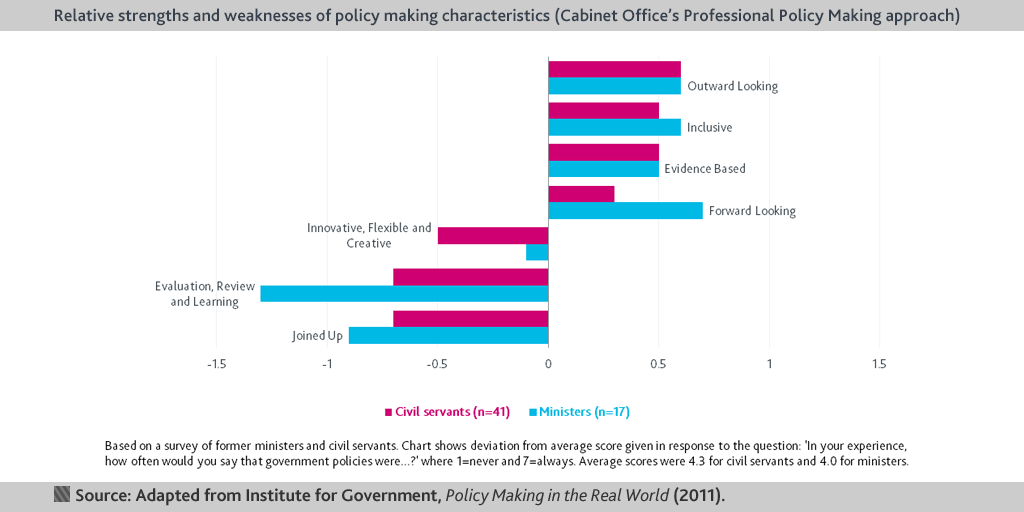

What can be done to improve the current situation around data and policy-making? Back in 2010, for our report Policy Making in the Real World, we asked ministers and civil servants to what extent policy making showed the ‘qualities’ laid out a decade earlier in Modernising Government.

- Topic

- Policy making

- Keywords

- Data and digital

- Publisher

- Institute for Government